People have gathered in this cave for at least 10,000 years

So far west out at sea that witty people claim the gulls here speak English, it’s midsummer on the Arctic Circle and we’re on Sanna Island in the municipality of Træna.

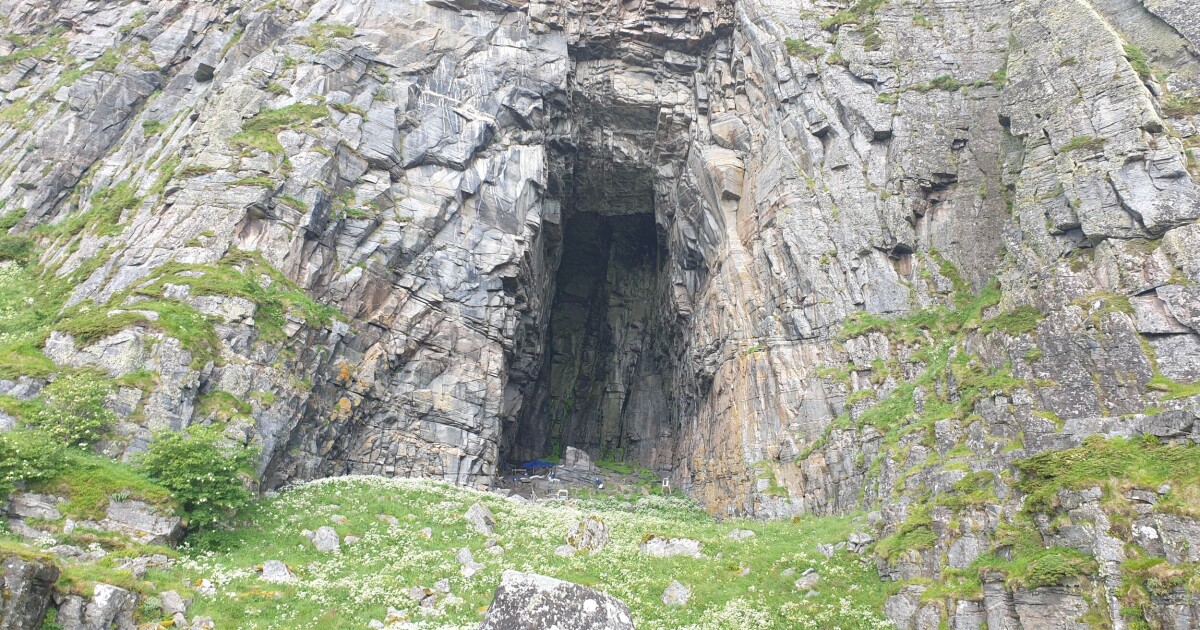

A 10 to 15 minute walk from the wharf is Kirkhellaren, a very famous cave where, through repeated ice ages, frost and sea have carved a cathedral out of a crevasse in the mountainside.

The cave is 32 meters high and 20 meters wide, with a rock in the center that forms a natural altar and has earned it the nickname “nature’s cathedral”. People have been gathering here for at least 10,000 years, making it one of the important meeting places along the Norwegian coast. The huge cave is perhaps the oldest meeting place on the Norwegian coast.

“Yes, it is the ideal place for the exchange of knowledge. People came here with the desire to meet other people,” says Mikael Fauvelle as he stands in a cave excavation site.

Fauvelle is a specialist in the interaction between prehistoric hunter-gatherers and he is an archaeologist at the University of Lund in Sweden. He studies the role of movement and mobility in ancient times, and this work has taken him to Træna and the Arctic Circle.

Important finds

Nearby, project manager Erlend Kirkeng Jørgensen nods. He has an impressive beard befitting his position as a researcher at the Far North Department of the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research at the Fram Centre. He supervises the excavations, which are quite spectacular.

“Look here,” said Jørgensen, holding an object the size of a small postage stamp. It came from the excavation site, through sieves and dishwashers.

“These are shards of pottery. You can see that a pattern has been created. We’re at a level that we go back about 3,000 years. Why is this little shard important? Well, the raw materials – l he clay and asbestos minerals used as a thinner/binder – and the know-how to convert them into useful objects all come from elsewhere. This shows that there was a seasonal migration to and from Træna. there was clay around Træna, it would have been so full of salt that it would crack quickly when fired. This means that the clay was brought here, probably from the mainland,” explains Jørgensen.

“This summer we found several pits filled with pottery and clay that show that ceramics were produced here in the cave,” he says.

A sailing brand

The dig site the researchers worked on this summer revealed surprisingly large amounts of bone remains, shells and burnt wood. This confirms that people have been living here for a long time and that they came here at least 9,000 years ago.

At the time, the floodplain was just outside the entrance to the cave and many of the islands visible today were below the surface of the sea. The sea was full of seals and fish, there so there was food just outside the cave, which in turn provided shelter. This made it a perfect place for people to set up camp.

The meeting place

“There weren’t many people living along the coast, but we know they were mobile. If we compare them to the Inuit of Greenland, we know that they were very mobile. The Inuit used kayaks and umikas and traveled all over Greenland. I think the same thing happened here. This is what I find most fascinating: people who lived along the Norwegian coasts could travel with similar boats over very large areas. You have to remember that people weren’t installed in the way that later became common. They followed the resources and the seasons, and in this way they acquired new knowledge. But not only that, people needed to meet, exchange goods, acquire knowledge and find a partner,” explains Fauvelle.

Fauvelle, who has published research on ancient gathering points in the United States and Mexico, is clear in his view that Kirkhellaren served as a key meeting place along the Norwegian coast.

Sanna Island is also home to the iconic Trænstaven mountain. Jutting 338 meters above the sea, it is one of the most visible and well-known sailing marks along the Norwegian coast and stands out clearly from the weather-worn beaches that characterize the outer coast of Helgeland.

“It’s an iconic place. It’s easy to get to, it can be seen from afar, the cave can hold a lot of people, and it’s a great place for big festivities and barters,” says Fauvell.

Seals were important

“And we have evidence that barter took place, either in the form of other goods or in the form of knowledge. The pottery shards show that the people here had learned the skills to fire clay Those who lived here hosted visitors and visited other places,” says Jørgensen.

The presence of seals was extremely important here in Sanna. The excavations unearthed thousands of seal bones and help to highlight how seals have been a valuable resource.

“Not only meat, but also fat and especially skins were important. They probably brought sealskins with them as trade goods. The tools we most often find here are various forms of leather processing scrapers. We found flint tools that were used to prepare seal skins,” says the project manager.

One could call the field excavated this summer the “dump” of the cave. This is where the people who lived here thousands of years ago threw the remains of fish, seals, birds and shells. Additionally, the researchers found cooking pits, hearths, and large amounts of burnt wood. Further on, a wall was discovered which had served as a windbreak.

Changes

Kirkhellaren and its contents have always been subject to change, both human and climatic. In recent times, the cave has served as an ideal habitat for sheep, which means that the surface of the cave was covered with a layer of sheep dung almost one meter thick. In 1982 sheep farming in Sanna ceased and the sheep droppings disappeared, and with them a protective layer for the archaeological treasures of the cave. The most significant impacts today are caused by human visitors and leaching. Every year, thousands of tourists visit Kirkhellaren, and during the Træna festival, a concert is held there.

“Given increased rainfall and warmer winters in our imminent future, biological conservation has become a pressing issue. One of the concrete aims of the project is to assess how we can best safeguard organic cultural heritage and its unique research potential,” says Jørgensen, adding:

“Coastal resources have been a prerequisite for life since humans first colonized the Norwegian coast. Nevertheless, the exploitation of coastal resources in the Stone Age receives relatively little attention in global research. The reason for this is that there are almost no preserved fragments of human resource exploitation that continuously cover the past 10,000 years. Kirkhellaren is unique in that the remains of meals preserved here date back to an exceptionally early point in history. Reconstructing marine food webs is interesting because humans are part of the ecosystem, and changes in stocks of important resources such as fish and seals can be expected to have consequences for human adaptation.

DNA should provide answers

After the summer fieldwork is completed, the excavation area has been filled in again, and the bottom of the cave will gradually return to its previous state. All samples collected during the work will be the subject of subsequent research and publications.

Among the 11 researchers who took part in this summer’s fieldwork are PhD students Håvard Kjellsen Bjerke, Emma Falkeid Eriksen and Lydia Hildebrand Furness from the University of Oslo. They will later analyze the DNA from the bone finds and then compare it with other DNA samples.

The material is so rich that even such small surveys will provide research data for many generations to come.